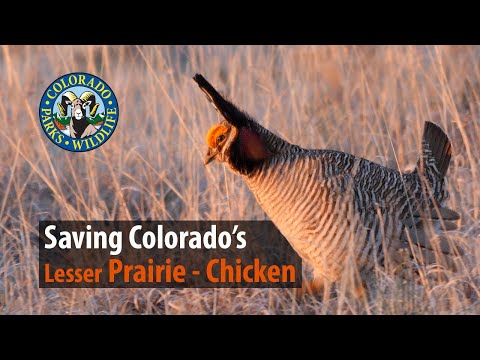

This wild chicken stomps its small feet so enthusiastically to attract a girlfriend that it tamps down its own section of grassland prairie.

Feathers that look like tiny horns pop up from its head, and bright-orange, balloon-like pockets inflate on the sides of its neck as it cackles and “booms.”

The male lesser prairie-chicken has been a springtime spectacle on the plains going back hundreds of years. Colorado, though, came close to losing them all.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife biologists counted just two male lesser prairie-chickens in 2016 in the Comanche National Grassland in southeastern Colorado, an area once abundant with the birds. Just across the Kansas stateline at the Cimarron National Grassland, there were only five. “At that point, we were afraid they were pretty much disappearing,” said Liza Rossi, a CPW wildlife biologist and the agency’s bird conservation coordinator. “We were really concerned about what was happening to our chickens in Colorado.”

That fall, Colorado Parks and Wildlife began a four-year relocation and tracking program that was the largest ever undertaken for lesser prairie-chickens, whose numbers have dwindled across the Great Plains due to drought and destruction of habitat. And this spring, bird biologists believe they have achieved success, although their work is not finished.

Now, there are at least 115 roosters and about the same number of hens on the grasslands in Baca County and neighboring Morton County, Kansas, Rossi said.

“This was our big, exciting year,” she said, describing how biologists hiding in blinds this spring have been thrilled as they count the number of surviving chicks. “It has been really positive in both Colorado and Kansas.”

One of the Baca County leks — a patch of prairie that males designate as a breeding zone, where they dance and boom through their throats trying to attract mates each spring — has 17 roosters. Colorado hasn’t had a lek that large since 2006, said CPW wildlife biologist Jonathan Reitz, who is based in Lamar. There are now 20 active leks, the “center of their universe,” in the region, he said.

Males birds typically create leks on top of ridges or hills, so their sound can carry farther, Reitz said. Roosters begin arriving in late February and stay until June, all the while cackling and fighting each other, dancing and stomping. “They work pretty hard to get those girls to pick them,” he said.

Females pop in for a day or two, take their pick of the pecking order, and then move on to look for a place to nest. Nesting is the most vulnerable time for a lesser prairie-chicken because their nests are on the ground in the buffalo grass, sought out not only by coyotes and foxes but hawks and snakes.

A female chicken nests for about a month, leaving only for a few minutes each day to find food — mainly small plants and insects. They can lay up to about 12, finely speckled eggs.

The habitat for the lesser prairie-chicken has been under stress for decades, going back even to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, when severe drought turned the landscape to choking dust. Added infrastructure — including oil pumps and wind farms — also have affected their habitat.

The number of chickens in Colorado already was dwindling in 2006 when the southeastern part of the state was smacked by a blizzard so destructive it killed masses of livestock, pronghorn and birds.

“It was a huge, huge blizzard,” Rossi said. “We never saw leks after that blizzard.”

Whatever chickens remained were again pummeled by severe weather — this time with three successive years of drought in 2012, 2013 and 2014. The chickens had little to eat, and the grasslands were so dried up that they offered scant protection from predators on the ground and in the sky.

Now, however, the grassland in Baca County is plenty healthy to sustain a large population of lesser prairie-chickens. It’s just that there weren’t enough of them left to reestablish on their own.

“It takes birds to make birds and we didn’t have any birds,” Reitz explained.

The chickens relocated to Colorado were captured near Scott City, Kansas. They were placed in pillow cases, tagged and checked for diseases, and then driven three hours away for release.

The process — entertaining to watch because of the speed of the biologists and the circus-tent-shaped drop-net that’s involved — starts at dawn and ends in the afternoon. The net is dropped over a lek of unsuspecting chickens, which instantly start to squawk and squirm when they are pinned to the ground.

Biologists take off running from their hiding spots, trying as quickly and as gently as possible to free the birds from the net and place them, one each, in pillow cases.

After the birds in the program were tagged each spring, and some fitted with GPS “backpacks,” they were placed in individual boxes inside an air-conditioned truck and driven west across Kansas and into southeastern Colorado.

Once in Baca County, biologists lifted the lids on the boxes and let the chickens fly.

At first they were unsure how many would stay. While the males were more likely to stay close by, the female chickens began flying concentric circles around their new home, flying farther and farther out each time.

It was a shock to biologists that some of the chickens put on 250 miles, flying over Oklahoma and Kansas, before returning to nest within a few miles of where CPW and partnering biologists with the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism had dropped them off. “Those birds are exploring, mapping out their area and getting their bearings,” Reitz said. “I didn’t anticipate that they would move that much.”

Biologists also were surprised to see how well lesser prairie-chickens could find each other on the landscape. When the scientists found one bird — either by GPS or by a necklace transmitter that biologists tracked via ground or by airplane — that bird usually had a buddy close by. About 40 chickens per year were fitted with a GPS backpack, which collects 10 locations per bird, per day. To find a bird wearing a necklace transmitter, the less-expensive tracking option, biologists need to drive within about a half-mile or fly within about seven miles of the chicken.

Reitz said wildlife biologists had no hard data to rely on as they planned the relocation, and past projects did not bode well. In the early 1990s, the department relocated about 100 Kansas chickens to the Pueblo area, and then a hunter in Garden City, Kansas, harvested one — proof the bird had just flown home.

A relocation project in the 1970s was written off because it didn’t seem that many of the chickens stayed put. No more than two leks were ever active in Baca County after the transfer. “Any project that had been done, there were giant question marks,” Reitz said. “We didn’t know how they would respond to being moved.”

But biologists learned this time — because this project included much more sophisticated tracking technology — that some of the chickens ended up nesting 12 or 15 miles away from where they were set free.

In the past four years, Colorado wildlife biologists have relocated more than 400 birds. Some died because of the stress of being moved to a new environment. Some died because of regular mortality, including being eaten by coyotes or eagles during nesting season.

“This is the largest translocation that has ever been done with lesser prairie-chickens,” Rossi said. “We knew we would have some amount of mortality.”

Still, with at least 230 chickens at the new location, including many that were born there, the program is considered successful. “It’s too early to tell long-term, but we were lucky,” Rossi said. “We are in a much better place if a drought were to come again.”

The lesser prairie-chicken, part of the grouse family, is about 15 inches tall. It’s similar to a pheasant but can fly farther. They look similar to the greater prairie-chicken (found in northeastern Colorado) but have brighter orange on their necks. It’s been illegal to hunt lesser prairie-chickens in Colorado for decades, but hunting of greater prairie-chickens is allowed in six counties.