Landowners who own the tops of Colorado’s Mount Lincoln, Mount Democrat and Mount Bross on Thursday closed access to the trio of Mosquito Range fourteeners.

The closure triggered an upswell of lamentations from Colorado’s peak-bagging community. But the closure is expected to last only this month.

“It is a temporary closure,” said Julie Mach, conservation director with the Colorado Mountain Club, who has worked for years with landowners in the Mosquito Range to protect both access and private property.

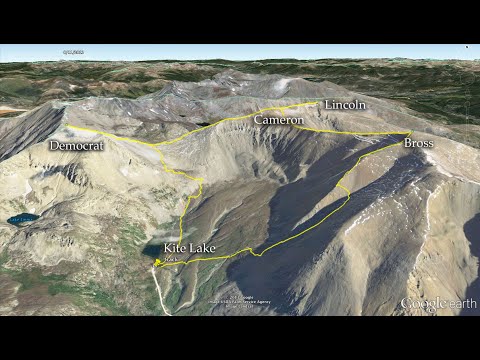

It is illegal to access the summit of Mount Bross, but landowners have allowed access to Mount Democrat and Mount Lincoln via a trail that starts at Kite Lake and loops around the three fourteeners. The landowners for many decades have worried about liability. There are mining structures and open pits all over the peaks.

One property owner told Lloyd Athearn, the head of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, about seeing a family off the loop trail a couple years ago.

“The dad was holding his son by the ankles, dangling him over a mine opening. The son had a flashlight and dad was asking what he could see,” Athearn said. “So yeah, there are some legitimate concerns about liability up there.”

Read more outdoors stories from The Colorado Sun.

The landowners have closed access to the peaks before, but reopened them after reaching agreements with land managers, fourteener trail groups and the Town of Alma. The liability concerns of the landowners spiked anew in 2019, when a federal court upheld a $7.3 million verdict awarded to a Colorado Springs mountain biker who crashed into a sinkhole on a washed-out trail at the U.S. Air Force Academy.

In the case involving injured cyclist, James Nelson, the Air Force Academy argued it was protected from damages under the Colorado Recreational Use Statute, which provides immunity to land owners who let people recreate on their land at no charge. But the statute does not provide liability if a landowner knows a dangerous condition exists and demonstrates a “willful or malicious failure” to guard or warn visitors about the dangers.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in February 2019 upheld several previous court decisions, ruling that Air Force Academy “failed to provide a justifiable excuse for its willful failure to guard or warn against the likely harm posed by the sinkhole.”

“That case certainly rekindled their concerns about liability,” Mach said.

John Reiber has owned mining claims all over Mount Lincoln, Mount Democrat and Mount Bross for decades. In that time he has worked with the Colorado Mountain Club, Colorado Fourteeners Initiative and the Town of Alma to protect recreational access to the peaks. He allowed construction of a trail on his property on the flanks of Mount Bross, but the trail does not go to the summit, because other landowners there do not allow hiking on their property.

The Colorado Fourteener Initiative’s annual use report shows 20,000 to 25,000 hikers a year climb the three peaks, often also scaling the 14,238-foot Cameron Peak, which does not rank as an official fourteener because it does not climb more than 300 feet from an adjacent saddle. That loop is informally known as the Decalibron.

In a June 2020 online discussion with the Colorado Mountain Club, Reiber outlined his concerns about liability and impacts from increasing traffic on the peaks.

After closing trails to the peaks in 2004, Reiber and his fellow landowners in 2006 reached an agreement to restore access with the Town of Alma, which leased about 3,900 acres around the three fourteeners. The deal — which is anchored in Colorado’s recreational use statute — alleviated some, but not all, landowner concerns about liability, Reiber said in an online discussion last summer.

“From time to time I check with an attorney on that level of protection and I have been recently advised it’s not as good as it used to be,” said Reiber, who could not be reached on Friday.

The Alma lease requires that hikers must remain on the trail and can’t remove materials, damage mining property, leave trash or make fires. The lease does not allow access to the top of Mount Bross.

In his presentation to Colorado Mountain Club members, Reiber showed maps that hikers could use to determine the boundaries between public and private land in the Mosquito Range. Then he scrolled through pictures of a gate ripped off a mine entrance on Lincoln, right next to a “No Trespassing” sign. He scrolled through photographs showing a line of hikers heading to the summit of Mount Bross on marked private property, including off-road-vehicles heading up to the summit. He described vandalism, stolen mine equipment, illegal fires, shooting and trash on his property.

“A lot of this is education,” he said. “I think that’s a never-ending opportunity. If people could be educated as to where they are at and respect that private property, I think through that we can work to keep these peaks open for everyone to enjoy.”

Alex Derr last August joined landowners and representatives from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative and the Colorado Mountain Club on a hike up Lincoln and Democrat. His master’s thesis in environmental policy at CU Denver studies access and liability issues swirling around the Mosquito Range, where pretty much the entire ridgeline is a collection of privately owned mining claims.

As they hiked, a dozen people on ATVs navigated around a gate and “no motorized access” signs and started throttling across the tundra. The owners chased them down and the drivers apologized, saying they were unaware they were on private land, Derr said.

“That was a real turning point for me,” said Derr, whose blog provides maps and guides to the state’s highest peaks. “I could really see the owners’ frustrations. If you want your land preserved and protected, but you don’t want to put up fences and keep everyone out, you are really stuck between a rock and a hard place.”

Both Mach, with the Colorado Mountain Club, and Athearn, with Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, feel confident access will be restored by June 1, which is when snow begins melting enough for hikers to actually start reaching peaks.

But when access is restored, advocates are pleading with hikers to help prevent a longer or even permanent closure.

“The landowners are supportive of recreation and they want to be able to keep the peaks open so it’s really contingent on recreationists to be responsible and stay on the trail,” Mach said.

Athearn, who has worked with Reiber, suspects the landowner may be using the temporary closure to affirm their property rights and prevent a prescriptive easement. (That’s when unfettered access through private property without permission lasts so long that it becomes a sort of de facto right of way.)

“This is a courtesy closure reminding people that he allows them to access his private land,” Athearn said. “It is his private land and he has been very accommodating and generous over the years, given that a lot of people behave irresponsibly up there.”